| The Spanish Inquisition:

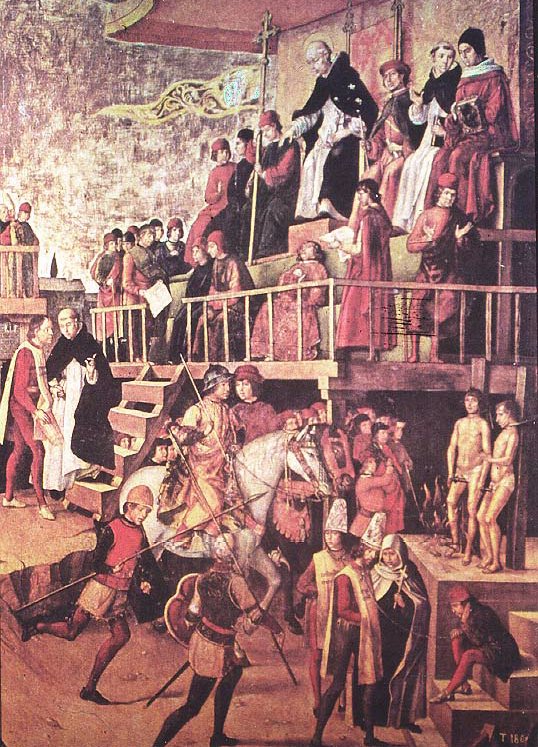

Killing Non-Christians for the Mother Church By Suzanne MacNevin When most people in North America (with the exception of Mexico) think of the Spanish Inquisition, they think of one thing: The line from Monty Python. "No one expects the Spanish Inquisition!" When asked what people actually think it was about, a large number of people use the words "witch hunt", but the words "killing jews" and "killing muslims" never seems to cross their minds. We can blame this upon the poor education that people in North America actually receive when it comes to history. History? Boring! Tell me when the teacher is done blabbing... Zzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzz... And because most people in North America think of history being boring (especially any history that isn't American), then American students don't really get taught much. The American history books start with Columbus discovering Cuba and usually end sometime in the Clinton era. Canadian history books are not much better. They usually start with the Vikings meeting Native Canadians and ends somewhere in the Chretien or Trudeau eras. Thus its no small surprise that people don't realize that the Spanish Inquisition was part of the third largest genocide in history. The largest genocide being the near extinction of Native Americans (in both North and South America) and the 2nd largest being the Jewish Holocaust in WWII. Such mass genocides are shameful both to the religions and to the races that support them. It is no laughing matter, especially in a post 9/11 culture where the right-wing Christian culture of America is supporting a move by the Bush presidency against the Muslim world. If it was a Jewish country that had oil, would we still be going to war? The Spanish Inquisition was a legally constituted court decreed by Sixtus IV's Papal Bull and implemented under Ferdinand and Isabella of Castile beginning in 1478. As Christian European monarchs regained control of Spain from Muslim rulers, the Christian Monarchy gradually imposed and enforced certain legal restrictions on non-Catholics. Spaniards who were not Catholics were not allowed into any of the major professions. Similarly, non-Catholics were forbidden from civil service by royal decree. Other legal and property rights depended on being baptized as did entrance into schools and general social standing. Many Muslims and Jews in Spain went along with the Crown in order to keep or get jobs, be considered part of Spanish society or simply to comply with the obvious wishes of the government. Many conversos (people who had converted from one religion to Christianity) were secular by upbringing and had little or no connection to their abandoned religions. But many who had converted during and after the massacres of 1391 did it simply to avoid death and had held onto what was, by 1478, more than a thousand years of Jewish culture and tradition in Spain. The Crown and the Vatican were concerned with the idea of converts following non-Christian ways of life. There was also a realization in Spain and Rome that large amounts of wealth had been looted in 1468 and 1473 along with concern that those proceeds should have gone to the government and the Church. Certain behaviors (some actual religious practices - others created by the Inquisitors) were labeled by the Church as “Judaising” and were strictly prohibited under punishment of death. As of 1478, any convert suspected or accused (however haphazardly) of Judaising was tried and put through an “act of faith” (auto de fe), the result of which was always one form of horrible punishment or another. None of the accused was found innocent - the only two possible outcomes of the Church’s would-be trials were guilt by admission and guilt with denial, the latter being cause for Church and State sponsored execution. Certain Church historians have recently asserted that anti-Semitism was not one of the main motivators for Rome or Spain, pointing out that the Inquisition only targeted converted Jews accused of Judaising, not Jews who refused to convert. This argument seems less convincing in view of Ferdinand’s expulsion of the Jews (including and especially the ones who never converted) from the country of Spain in 1492. Any Jew or Muslim who had not converted and did not leave Spain was thereafter legally executed by the Crown with the Pope’s knowledge and approval. Many practicing Jews and Muslims had left Spain by early August of 1492 and any who did not leave were executed soon afterwards. Many of the converts were killed anyway when they were accused of heresy thereafter, usually people who a) had money and/or b) could be accused of having a Jewish or Muslim ancestor, whether it was true or not. The Spanish Inquisition was loosely connected with the Holy Office of the Inquisition into Heretical Depravity (which lacked the manpower/resources to conduct the inquisition properly). The Holy Office of the Inquisition into Heretical Depravity was responsible for many other inquisitions, largely targeting Christian dissenters, secular freethinkers and Jews. The Inquisition was removed during Napoleonic rule (1808–1812), but reinstituted when Ferdinand VII of Spain recovered the throne. It was officially ended on 15 July 1834. Schoolmaster Cayetano Ripoli, garroted to death in Valencia on July 26, 1826 (allegedly for teaching Deist principles), was the last person executed by the Spanish Inquisition.  The Catholic Church's holy terrorA docudrama based on secret Vatican files shows people literally arguing for their lives By Brian Bethune "Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition!" Monty Python famously joked in 1970, and we all laughed, probably quite unaware that only a century earlier the Holy Office of the Inquisition into Heretical Depravity -- to give the Roman Catholic Church's enforcer its proper, ominous name -- was still hard at work. For 600 years the Inquisition was a real and dangerous presence in the lives of millions and, in the minds of those the Church persecuted as enemies of the true faith -- Christian dissenters, secular freethinkers and Jews -- the ultimate icon of religious tyranny. Even now its name conjures up nightmares of Pit and Pendulum-style torture and victims burning at the stake. So potent is the image that it's never been easy to separate the Inquisition of myth from the Inquisition of history. But the Vatican's 1998 decision to open up its files -- made by Pope Benedict XVI when he was still the cardinal in charge of the Inquisition's archives -- finally allowed historians to make a start. And not just historians. The Vatican announcement also caught the imagination of American filmmaker David Rabinovitch. "My first thought was, 'There's got to be some stories there,' " he told reporters. And so it proved. His four-part docudrama, Secret Files of the Inquisition, which began airing on Vision TV on Feb. 1, brings to life chilling incidents through the actual words -- spoken by an all-Canadian vocal cast, including narrator Colm Feore -- of a kaleidescope of victims, people literally arguing for their lives. During the 15th- and 16th-century Inquisition in Spain, which was primarily motivated by a profound anti-Semitism, the main targets were conversos -- Jews who had converted to Christianity in recent years, often at the point of a sword, or their descendants. Spanish Catholics suspected most, if not all, of them of still being secret Jews. (Ironically, professing Jews were not directly subject to the Inquisition's tender mercies: its legal mandate was to root out heresy among Christians.) So the interrogators obsessed over the telltale minutiae of everyday life, particularly food. "There was salt pork on the table, but she ate none," was the damning testimony of one witness about a converso. There were endless questions about recipe ingredients, so much so that one historian has created a medieval cookbook solely from inquisitorial records. Scholars tend to doubt the plausibility of most accusations of secret Judaism, but sometimes the charges were true. Rabinovitch's story centres on a young woman, baptized Juana but called Cinfa by her family members who had for decades lived a dangerous double existence, trying to preserve their lives and their ancestral faith. Betrayed by neighbours, Cinfa remained defiant to the end, her last words to her torturers among the most stirring in the records: "You are the ones who are lost. We are the fortunate ones. And don't call me Juana -- my name is Cinfa." In the French Pyrenean village of Montaillou, inquisitors turned up a soap opera-worthy web of heresy, local politics and sexual jealousy in 1308, most of it swirling about Pierre Clergue, village priest, heretic sympathizer and local Casanova. Clergue's conquests included the local noblewoman, wooed through his unorthodox theology: he assured her that God had forgiven their sexual trespasses even before they happened. It is impossible to tell, in fact, if Clergue's heretical beliefs were genuine or simply aids to seduction. A French historian once wrote that it seemed every woman in the village had slept with the priest, wanted to sleep with him, or had deloused him. (The last was a common medieval lovers' intimacy, one with million-year-old roots -- consider chimpanzee foreplay -- that modern hygiene has thankfully abolished.) In the end, only one villager went to the stake out of more than 100 interrogated; many others were imprisoned or sentenced to wear yellow crosses on their clothing, the reconciled heretic's equivalent of a Jew's yellow star. Rabinovitch argues that his rich source material proves that "evil loves to document itself." But that's not really true. Far more often, evil likes to hide its tracks, as any historian who has tried to find a paper trail linking Adolf Hitler to Auschwitz will attest. Those meticulous notes were taken by men convinced of their own righteousness. What those records do show is the fate of individuals caught up in great historical storms: most are accidental and half-hearted participants, but all of them have to decide whether to bend with the wind or stand and die for their beliefs.

|

|